Observer

Define a one-to-many dependency between objectsso that when one object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

Introduction

Observer Pattern is a design pattern belonging to the Behavioral Pattern group

Define one-to-many dependencies between objects so that when an object changes state, all its dependencies are notified and updated automatically.

An object can notify an unlimited number of other objects

They are like when we subscribe or press the notification bell for a Youtube channel, when that channel has a new video (changes status), they will send notifications (automatically) to us.

Problem

Imagine that you have two types of objects: a Customer and a Store. The customer is very interested in a particular brand of product (say, it’s a new model of the iPhone) which should become available in the store very soon.

The customer could visit the store every day and check product availability. But while the product is still en route, most of these trips would be pointless.

On the other hand, the store could send tons of emails (which might be considered spam) to all customers each time a new product becomes available. This would save some customers from endless trips to the store. At the same time, it’d upset other customers who aren’t interested in new products.

It looks like we’ve got a conflict. Either the customer wastes time checking product availability or the store wastes resources notifying the wrong customers.

Solution

The object that has some interesting state is often called subject, but since it’s also going to notify other objects about the changes to its state, we’ll call it publisher. All other objects that want to track changes to the publisher’s state are called subscribers.

The Observer pattern suggests that you add a subscription mechanism to the publisher class so individual objects can subscribe to or unsubscribe from a stream of events coming from that publisher. Fear not! Everything isn’t as complicated as it sounds. In reality, this mechanism consists of 1) an array field for storing a list of references to subscriber objects and 2) several public methods which allow adding subscribers to and removing them from that list.

Now, whenever an important event happens to the publisher, it goes over its subscribers and calls the specific notification method on their objects.

Real apps might have dozens of different subscriber classes that are interested in tracking events of the same publisher class. You wouldn’t want to couple the publisher to all of those classes. Besides, you might not even know about some of them beforehand if your publisher class is supposed to be used by other people.

That’s why it’s crucial that all subscribers implement the same interface and that the publisher communicates with them only via that interface. This interface should declare the notification method along with a set of parameters that the publisher can use to pass some contextual data along with the notification.

If your app has several different types of publishers and you want to make your subscribers compatible with all of them, you can go even further and make all publishers follow the same interface. This interface would only need to describe a few subscription methods. The interface would allow subscribers to observe publishers’ states without coupling to their concrete classes.

Real-World Analogy

If you subscribe to a newspaper or magazine, you no longer need to go to the store to check if the next issue is available. Instead, the publisher sends new issues directly to your mailbox right after publication or even in advance.

The publisher maintains a list of subscribers and knows which magazines they’re interested in. Subscribers can leave the list at any time when they wish to stop the publisher sending new magazine issues to them.

Structure

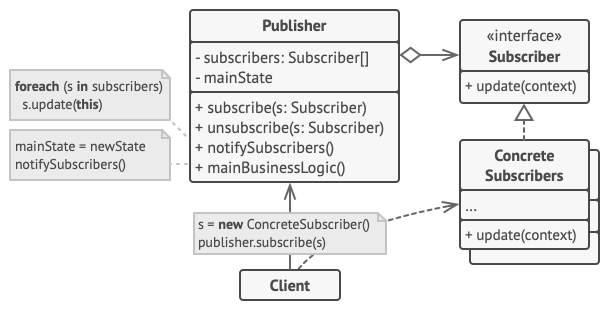

The Publisher issues events of interest to other objects. These events occur when the publisher changes its state or executes some behaviors. Publishers contain a subscription infrastructure that lets new subscribers join and current subscribers leave the list.

When a new event happens, the publisher goes over the subscription list and calls the notification method declared in the subscriber interface on each subscriber object.

The Subscriber interface declares the notification interface. In most cases, it consists of a single

updatemethod. The method may have several parameters that let the publisher pass some event details along with the update.Concrete Subscribers perform some actions in response to notifications issued by the publisher. All of these classes must implement the same interface so the publisher isn’t coupled to concrete classes.

Usually, subscribers need some contextual information to handle the update correctly. For this reason, publishers often pass some context data as arguments of the notification method. The publisher can pass itself as an argument, letting subscriber fetch any required data directly.

The Client creates publisher and subscriber objects separately and then registers subscribers for publisher updates.

Advantages & disadvantages

Advantage

Ensuring Open/Closed Principle (OCP): Allows changing Subject and Observer independently. We can reuse Subjects without reusing Observers and vice versa. It allows adding Observers without modifying another Subject or Observer.

Establish relationships between objects at runtime.

State changes in one object can be communicated to other objects without having to keep them too tightly coupled.

Unlimited number of Observers

Disadvantage

Unexpected update: Because the Observers are unaware of each other's presence, it can incur the overhead of changing Subjects.

Subscribers are notified in random order.

When to use it

Use Observer Pattern when we want:

State changes in one object need to be communicated to other objects without keeping them too tightly coupled.

Need to expand the project with minimal changes.

When abstraction has two aspects, one depends on the other. Encapsulating these aspects in different objects allows you to change and reuse them independently.

When changing one object requires changing other objects, and you don't know how many objects need to be changed.

When an object communicates to other objects without knowing what that object is, in other words, avoid being tightly coupled.

Applicability

Use the Observer pattern when changes to the state of one object may require changing other objects, and the actual set of objects is unknown beforehand or changes dynamically.

You can often experience this problem when working with classes of the graphical user interface. For example, you created custom button classes, and you want to let the clients hook some custom code to your buttons so that it fires whenever a user presses a button.

The Observer pattern lets any object that implements the subscriber interface subscribe for event notifications in publisher objects. You can add the subscription mechanism to your buttons, letting the clients hook up their custom code via custom subscriber classes.

Use the pattern when some objects in your app must observe others, but only for a limited time or in specific cases.

The subscription list is dynamic, so subscribers can join or leave the list whenever they need to.

How to Implement

Look over your business logic and try to break it down into two parts: the core functionality, independent from other code, will act as the publisher; the rest will turn into a set of subscriber classes.

Declare the subscriber interface. At a bare minimum, it should declare a single

updatemethod.Declare the publisher interface and describe a pair of methods for adding a subscriber object to and removing it from the list. Remember that publishers must work with subscribers only via the subscriber interface.

Decide where to put the actual subscription list and the implementation of subscription methods. Usually, this code looks the same for all types of publishers, so the obvious place to put it is in an abstract class derived directly from the publisher interface. Concrete publishers extend that class, inheriting the subscription behavior.

However, if you’re applying the pattern to an existing class hierarchy, consider an approach based on composition: put the subscription logic into a separate object, and make all real publishers use it.

Create concrete publisher classes. Each time something important happens inside a publisher, it must notify all its subscribers.

Implement the update notification methods in concrete subscriber classes. Most subscribers would need some context data about the event. It can be passed as an argument of the notification method.

But there’s another option. Upon receiving a notification, the subscriber can fetch any data directly from the notification. In this case, the publisher must pass itself via the update method. The less flexible option is to link a publisher to the subscriber permanently via the constructor.

The client must create all necessary subscribers and register them with proper publishers.

Relations with Other Patterns

Chain of Responsibility, Command, Mediator and Observer address various ways of connecting senders and receivers of requests:

Chain of Responsibility passes a request sequentially along a dynamic chain of potential receivers until one of them handles it.

Command establishes unidirectional connections between senders and receivers.

Mediator eliminates direct connections between senders and receivers, forcing them to communicate indirectly via a mediator object.

Observer lets receivers dynamically subscribe to and unsubscribe from receiving requests.

The primary goal of Mediator is to eliminate mutual dependencies among a set of system components. Instead, these components become dependent on a single mediator object. The goal of Observer is to establish dynamic one-way connections between objects, where some objects act as subordinates of others.

There’s a popular implementation of the Mediator pattern that relies on Observer. The mediator object plays the role of publisher, and the components act as subscribers which subscribe to and unsubscribe from the mediator’s events. When Mediator is implemented this way, it may look very similar to Observer.

When you’re confused, remember that you can implement the Mediator pattern in other ways. For example, you can permanently link all the components to the same mediator object. This implementation won’t resemble Observer but will still be an instance of the Mediator pattern.

Now imagine a program where all components have become publishers, allowing dynamic connections between each other. There won’t be a centralized mediator object, only a distributed set of observers.

Last updated