Command

Encapsulate a request as an object, thereby letting you parameterize clients with different requests, queue or log requests, and support undoable operations.

Introduction

Command (also known as Action, Transaction) is a design pattern belonging to the Behavioral Pattern group.

The Command pattern is a pattern that allows you to convert a request into an independent object containing all information about the request. This transformation allows you to parameterize methods with different requirements such as log, queue (undo/redo), translation.

The concept of Command Object is like an intermediate class created to store commands and state of the object at a certain time.

Command translated means to give orders. Commander means commanding, this person does not do anything but only orders others to do it. Thus, there must be someone to receive orders and execute them. The person giving the command needs to provide a class that encapsulates the commands. The recipient of the command needs to distinguish which interfaces to execute the command correctly.

Frequency of use: quite high

Problem

Imagine that you’re working on a new text-editor app. Your current task is to create a toolbar with a bunch of buttons for various operations of the editor. You created a very neat Button class that can be used for buttons on the toolbar, as well as for generic buttons in various dialogs.

While all of these buttons look similar, they’re all supposed to do different things. Where would you put the code for the various click handlers of these buttons? The simplest solution is to create tons of subclasses for each place where the button is used. These subclasses would contain the code that would have to be executed on a button click.

Before long, you realize that this approach is deeply flawed. First, you have an enormous number of subclasses, and that would be okay if you weren’t risking breaking the code in these subclasses each time you modify the base Button class. Put simply, your GUI code has become awkwardly dependent on the volatile code of the business logic.

And here’s the ugliest part. Some operations, such as copying/pasting text, would need to be invoked from multiple places. For example, a user could click a small “Copy” button on the toolbar, or copy something via the context menu, or just hit Ctrl+C on the keyboard.

Initially, when our app only had the toolbar, it was okay to place the implementation of various operations into the button subclasses. In other words, having the code for copying text inside the CopyButton subclass was fine. But then, when you implement context menus, shortcuts, and other stuff, you have to either duplicate the operation’s code in many classes or make menus dependent on buttons, which is an even worse option.

Solution

Good software design is often based on the principle of separation of concerns, which usually results in breaking an app into layers. The most common example: a layer for the graphical user interface and another layer for the business logic. The GUI layer is responsible for rendering a beautiful picture on the screen, capturing any input and showing results of what the user and the app are doing. However, when it comes to doing something important, like calculating the trajectory of the moon or composing an annual report, the GUI layer delegates the work to the underlying layer of business logic.

In the code it might look like this: a GUI object calls a method of a business logic object, passing it some arguments. This process is usually described as one object sending another a request.

The Command pattern suggests that GUI objects shouldn’t send these requests directly. Instead, you should extract all of the request details, such as the object being called, the name of the method and the list of arguments into a separate command class with a single method that triggers this request.

Command objects serve as links between various GUI and business logic objects. From now on, the GUI object doesn’t need to know what business logic object will receive the request and how it’ll be processed. The GUI object just triggers the command, which handles all the details.

The next step is to make your commands implement the same interface. Usually it has just a single execution method that takes no parameters. This interface lets you use various commands with the same request sender, without coupling it to concrete classes of commands. As a bonus, now you can switch command objects linked to the sender, effectively changing the sender’s behavior at runtime.

You might have noticed one missing piece of the puzzle, which is the request parameters. A GUI object might have supplied the business-layer object with some parameters. Since the command execution method doesn’t have any parameters, how would we pass the request details to the receiver? It turns out the command should be either pre-configured with this data, or capable of getting it on its own.

Let’s get back to our text editor. After we apply the Command pattern, we no longer need all those button subclasses to implement various click behaviors. It’s enough to put a single field into the base Button class that stores a reference to a command object and make the button execute that command on a click.

You’ll implement a bunch of command classes for every possible operation and link them with particular buttons, depending on the buttons’ intended behavior.

Other GUI elements, such as menus, shortcuts or entire dialogs, can be implemented in the same way. They’ll be linked to a command which gets executed when a user interacts with the GUI element. As you’ve probably guessed by now, the elements related to the same operations will be linked to the same commands, preventing any code duplication.

As a result, commands become a convenient middle layer that reduces coupling between the GUI and business logic layers. And that’s only a fraction of the benefits that the Command pattern can offer!

Real-World Analogy

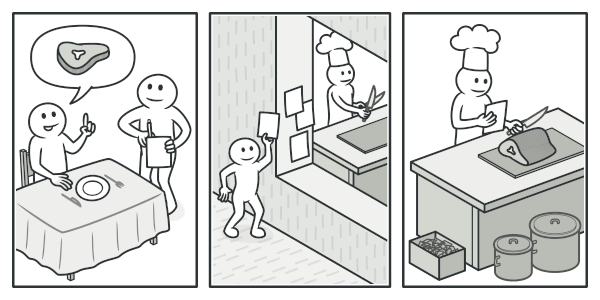

After a long walk through the city, you get to a nice restaurant and sit at the table by the window. A friendly waiter approaches you and quickly takes your order, writing it down on a piece of paper. The waiter goes to the kitchen and sticks the order on the wall. After a while, the order gets to the chef, who reads it and cooks the meal accordingly. The cook places the meal on a tray along with the order. The waiter discovers the tray, checks the order to make sure everything is as you wanted it, and brings everything to your table.

The paper order serves as a command. It remains in a queue until the chef is ready to serve it. The order contains all the relevant information required to cook the meal. It allows the chef to start cooking right away instead of running around clarifying the order details from you directly.

Structure

Components in the model:

Command: is an interface or abstract class, containing an abstract method that executes an operation. Request will be packaged as Command.

ConcreteCommand: are implementations of Command. Defines an association between a Receiver object and an action. Execute execute() by calling the deferred operation on the Receiver.

Client: receives the request from the user, packages the request into an appropriate ConcreteCommand and sets up its receiver.

Invoker: receives ConcreteCommand from Client and calls execute() of ConcreteCommand to execute the request.

Receiver: this is the component that actually handles the business logic for the case request. In the execute() method of ConcreteCommand we will call the appropriate method in the Receiver.

Advantages & disadvantages

Advantage

Ensure the Single Responsibility principle

Ensure Open/Closed principle

Undo can be performed

Reduce connection dependency between Invoker and Receiver

Allows packaging of requests into objects, easily transferring data between system components

Disadvantage

Makes the code more complex, creating new classes that complicate the source code.

When to use it

Below we can list some cases where we should consider using the Command pattern:

When you need to parameterize objects according to an action to perform (turn action into parameter)

When it is necessary to create and execute requests at different times (delay action)

When you need to support undo, log, callback or transaction features

Coordinate multiple Commands together in order

Applicability

Use the Command pattern when you want to parametrize objects with operations.

The Command pattern can turn a specific method call into a stand-alone object. This change opens up a lot of interesting uses: you can pass commands as method arguments, store them inside other objects, switch linked commands at runtime, etc.

Here’s an example: you’re developing a GUI component such as a context menu, and you want your users to be able to configure menu items that trigger operations when an end user clicks an item.

Use the Command pattern when you want to queue operations, schedule their execution, or execute them remotely.

As with any other object, a command can be serialized, which means converting it to a string that can be easily written to a file or a database. Later, the string can be restored as the initial command object. Thus, you can delay and schedule command execution. But there’s even more! In the same way, you can queue, log or send commands over the network.

Use the Command pattern when you want to implement reversible operations.

Although there are many ways to implement undo/redo, the Command pattern is perhaps the most popular of all.

To be able to revert operations, you need to implement the history of performed operations. The command history is a stack that contains all executed command objects along with related backups of the application’s state.

This method has two drawbacks. First, it isn’t that easy to save an application’s state because some of it can be private. This problem can be mitigated with the Memento pattern.

Second, the state backups may consume quite a lot of RAM. Therefore, sometimes you can resort to an alternative implementation: instead of restoring the past state, the command performs the inverse operation. The reverse operation also has a price: it may turn out to be hard or even impossible to implement.

How to Implement

Declare the command interface with a single execution method.

Start extracting requests into concrete command classes that implement the command interface. Each class must have a set of fields for storing the request arguments along with a reference to the actual receiver object. All these values must be initialized via the command’s constructor.

Identify classes that will act as senders. Add the fields for storing commands into these classes. Senders should communicate with their commands only via the command interface. Senders usually don’t create command objects on their own, but rather get them from the client code.

Change the senders so they execute the command instead of sending a request to the receiver directly.

The client should initialize objects in the following order:

Create receivers.

Create commands, and associate them with receivers if needed.

Create senders, and associate them with specific commands.

Relations with Other Patterns

Chain of Responsibility, Command, Mediator and Observer address various ways of connecting senders and receivers of requests:

Chain of Responsibility passes a request sequentially along a dynamic chain of potential receivers until one of them handles it.

Command establishes unidirectional connections between senders and receivers.

Mediator eliminates direct connections between senders and receivers, forcing them to communicate indirectly via a mediator object.

Observer lets receivers dynamically subscribe to and unsubscribe from receiving requests.

Handlers in Chain of Responsibility can be implemented as Commands. In this case, you can execute a lot of different operations over the same context object, represented by a request.

However, there’s another approach, where the request itself is a Command object. In this case, you can execute the same operation in a series of different contexts linked into a chain.

Command and Strategy may look similar because you can use both to parameterize an object with some action. However, they have very different intents.

You can use Command to convert any operation into an object. The operation’s parameters become fields of that object. The conversion lets you defer execution of the operation, queue it, store the history of commands, send commands to remote services, etc.

On the other hand, Strategy usually describes different ways of doing the same thing, letting you swap these algorithms within a single context class.

Last updated